Amid pandemic, new police powers target migrants, sex workers and the poor

Amid pandemic, new police powers target migrants, sex workers and the poor

Law enforcement officers have been given more powers during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the people most affected are also the people most marginalized even in normal times: migrants, racialized peoples, sex workers, and the poor.

As discussed in this May 18 Media Co-op article, civil rights advocates and other organizations worry that allowing law enforcement officers to demand people’s identification will single out Black, Indigenous and poor people, which will increase the risk of migrants being stopped, arrested, and detained by immigration authorities.

The Canadian government is currently suspending refugee hearings and the deportation of migrants, the Toronto Star reported in March. Previously, the Immigration and Refugee Board had also canceled and postponed all in-person hearings and mediations until April 5. By April 19, after being released to avoid possible outbreaks, the number of immigration detainees in provincial jails and immigration holding centres had dropped by more than half, from 353 on March 17 to 147, Global News reported.

But that doesn’t mean that vulnerable groups won’t be harassed, says Noa Mendelsohn Aviv, the equality program director at the Canadian Civil Liberties Association.

Particularly at a disadvantage, she says, are street-bound people, including the homeless, a group that is “disproportionately in contact with the police.”

“We’re monitoring and seeing what needs to be done on the systemic level, because there are all the more… orders that grant powers to police and officers to go in and ask questions of people on the street who don’t have anywhere else to go,” she told the Media Co-op. “We’re looking at those interactions as they increase: the nature of people getting more tickets that they can’t possibly pay and their targeting… in ways that are unfair.”

On May 15, activists gathered under the Gardiner Expressway in Toronto to try to stop police from dismantling homeless encampments, BlogTO reported.

"What's happening right now is just so unnecessary. It's against common sense to be doing this right now," Jennifer Evans, one of the activists on-site told the publication. “They are robbing these people of their dignity and it's just offensive."

According to that article, an activist had placed herself in front of a bulldozer, prompting its operator to stop. The activists left after being promised nothing would happen that day, but “everything at Lakeshore had been bulldozed after they left,” according to that report.

The new law means all law enforcement including police officers, First Nations constables, special constables (such as TTC and community housing constables) and municipal bylaw enforcement officers can demand people hand over their ID if the cops have "reasonable grounds" to suspect they are breaking emergency measures.

This means there will be a lot more officers “who may not get the same training” as police do to know how to deal with the people they stop, says Aviv.

Vincent Wong, a research associate at the University of Toronto’s law school International Human Rights Program, says this leaves a lot of room for escalation.

"It often doesn't stop at a fine. It can (end) in an altercation that gets people arrested and jailed. (It’s) a really horrible order for a particular community,” he told tthe Media Co-op.

Though there is an official complaint system through which people can report grievances with the police, Aviv says the problem is that people “don’t have a lot of faith in it.”

“During the peak of carding, the stories that we heard suggested that really there’s not a lot of recourse for somebody who has had an unpleasant interaction with an officer,” she recalled. “So that [complaint system has] not been effective.”

More policing, more dangers

In 2018, a sex worker ran out of a massage parlor in panic after being assaulted by her client, recalls Elene Lam, the executive director at Butterfly: Asian and Migrant Sex Worker Support Network. Seeing the commotion, a nearby resident called the police. But when the cops got there, it was the worker who was ticketed for not wearing proper clothing instead of her client, who had left.

According to Lam, that is a far too common experience for sex workers, who face more harassment from police than they do from their own clients.

“The number one violence experienced by sex workers is not from perpetrators. It’s law enforcement,” she told the Media Co-op. “This community has a long history of being harmed and hurt and abused by law enforcement, including bylaw (officers) and the police.”

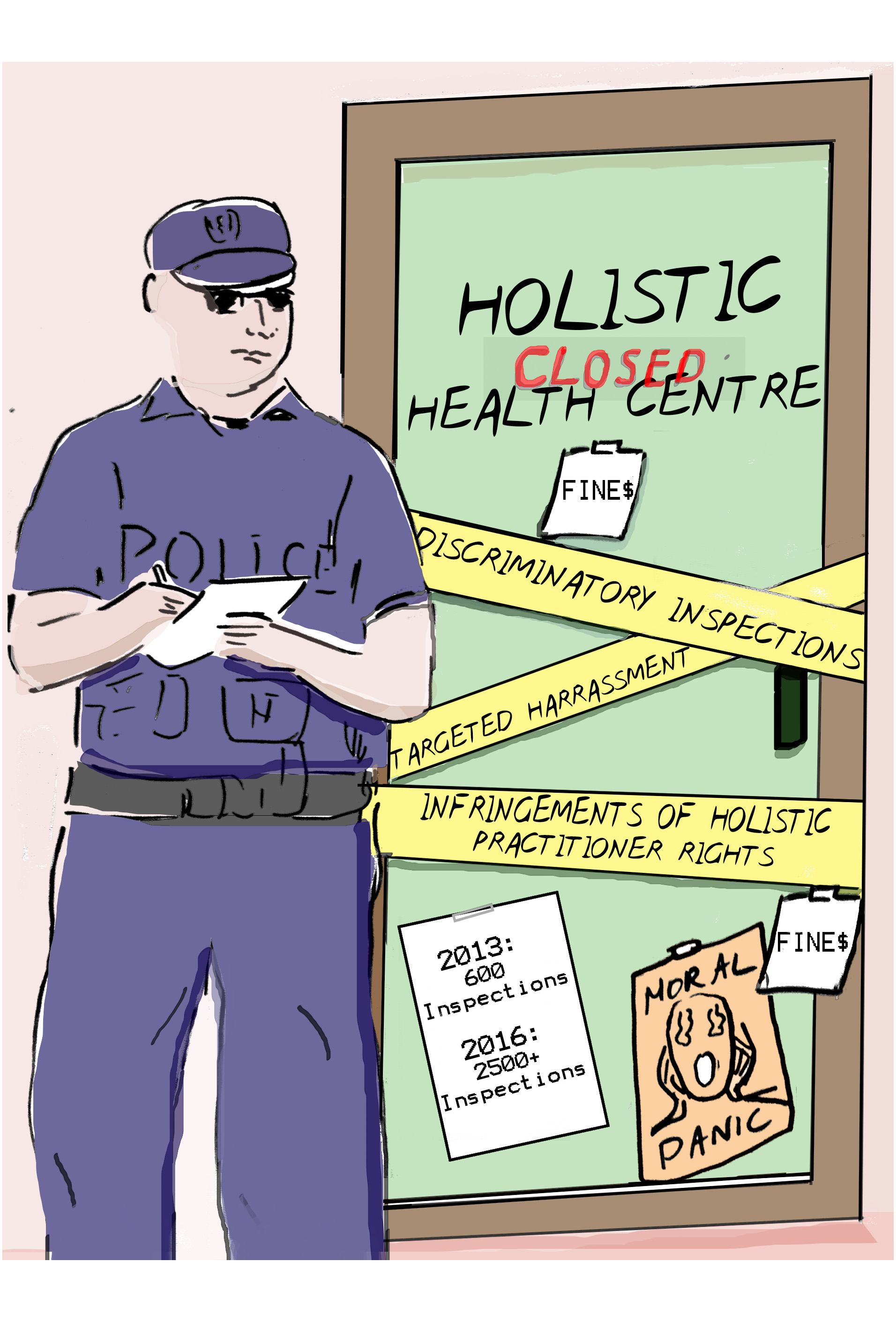

The Survey on Toronto Holistic Practitioner's Experiences with Bylaw Enforcement and Police, written by Lam, documents this history in depth. The report was published in 2018 by Butterfly, the Coalition Against Abuse By Bylaw Enforcement, the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, and the Holistic Practitioners Alliance.

The survey found that workers' "main concerns were inspections and/or raids (65.5%) and being fined and charged (44.8%)." It also found "[m]ore than one-third reported…[being] abused or harassed by bylaw enforcement or police officers," 22% had been insulted or verbally abused, and 12% were physically or sexually assaulted by law enforcement officers.

Furthermore, it stated that 60 percent of respondents had negative perceptions of bylaw enforcement and police officers; 40 percent felt that the officers did not respect them as workers; 37.8 percent expressed being treated as criminals; and 13 percent reported being unjustifiably punished. “Half described police officers as abusive, oppressive, or humiliating (53.6%), while a significant number perceived them as discriminatory (42.9%) and unreliable (25%)," the report reads.

“Bylaws themselves are problematic and enable bylaw enforcement and police officers to use their broad discretion to abuse and harass practitioners who work in spas and wellness centres."

The report thus concluded that “practitioners perceived these excessive practices of law enforcement officers to be the result of racial profiling and discrimination, rather than the promotion of workplace health and safety. This negative perception of law enforcement discourages practitioners from seeking help from them when experiencing difficult situations.”

Lam says that over 90 percent of Butterfly’s members are migrants, and that globally 60 percent of sex workers are migrants.

According to the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP), “migrant sex workers are rarely viewed as part of global labour migration flows. However, under the Migrant Workers Convention, sex workers who move across borders are indeed labour migrants, often driven to move in order to escape local inequalities (particularly economic and legal) in search of destinations that allow them to earn higher incomes, work safely, and live in a context where their human rights are respected.”

This, says Lam, means that it’s “mainly racialized people or the more marginalized people, and undocumented migrants (that) are being targeted.”

“So that also creates a lot of worry and panic to the community...(and) that’s why we don’t say policing can save their lives. Actually, policing makes the people have more dangers.”

More than just sex

In late April, CTV News reported that many sex workers had lost their income overnight as the pandemic hit, leaving many in desperate situations and unable to afford necessities. Some have even become homeless. Another report by Victoria News documented some of the “new risks” sex-workers are facing in Vancouver, including “desperation" leading to “sexualiced violence.”

“The reason that’s happening … is who knows what next week is going to bring us?” one sex worker speaking under a pseudonym told the publication. “Who knows what’s going to happen in two weeks? Sure they have a self-employed benefit but … we don’t know if that takes us into consideration.”

The government’s relief income during the pandemic does not apply to undocumented workers, leaving many sex workers to fend entirely for themselves.

Those who continue therefore do it for financial reasons, and are taking precautionary methods like asking clients screening questions and to shower beforehand.

But their work is essential for many of their clients, says Lam, because it’s not just about sex. Many clients are simply seeking friendship and some respect, she says, particularly during this pandemic.

“For many people, they may not have regular sex partner, so sex is still essential part of some people’s lives,” she said.

“(But) sex workers...also provide care and emotional support… Some people really need that service and support in this critical moment, no matter (whether it’s) physical or mental.”

Butterfly is providing those who are still working with Personal Protective Equipment such as masks, says Lam. A hotline that regularly offers its members translation services and helps them connect with various community resources has also been modified to help disseminate COVID-19 updates.

The hotline, which normally receives an average of 20 calls per week, received upwards of 500 calls and text messages the week the emergency order was passed, Lam says. Since then, the line still receives around 200 calls and texts per week.

Prioritize community, not policing

Governments have historically approached issues around sex work by throwing money into anti-trafficking programs.

Indeed, as the NSWP’s report states, because sex workers are often “painted as victims or criminals in discourses that conflate sex work with human trafficking [...] [t]heir human rights are often overlooked in favour of driving broader political agendas to restrict migration and criminalise sex work.”

This is due to the fact that “migrant workers are still stigmatised and silenced – in politics and media alike.”

According to Lam, what sex workers need are permanent protections from the government all year round in order to stop police harassment.

Butterfly’s 2018 report cited above made three sweeping recommendations: 1) “An end to excessive and discriminatory inspections and prosecutions of holistic centers and practitioners”; 2) “Thorough investigation into complaints against bylaw enforcement...and a guarantee that practitioners will not be punished”; 3) “A comprehensive review of current bylaws and enforcement policies...with meaningful participation of owners, practitioners, and other stakeholders.”

Resources should also be directed towards empowering “the capacity of the community and the supports they need,” Lam said.

These include income security and protection despite immigration status, social supports and benefits, and stopping the sharing of information with the CBSA.

Most importantly, says Lam, sex work must be decriminalized, “because criminalizing it makes people work underground, which means they cannot get any labour protections.”

In other words, what’s needed is a system that allows “people with (precarious) immigrantion status (to) access government funding without the fear of other kinds of consequences.”

“So (that) no matter COVID-19 or not, there is a lot of shelter and drop-in programs and sex worker support programs that help them connect with other community members.”

Likewise for other vulnerable groups, what's needed is a systemic overhaul in which links to community support groups are prioritized rather than over-policing.

That's why Aviv says the CCLA will “be on top of” the police, monitoring the situation closely to ensure the government doesn’t assume “powers that it doesn’t need.”

“Because our rights and freedoms are also important and they don’t go away in the pandemic,” she said.

“It’s even more important to...(make) sure that the powers that are exercised are necessary and proportionate now and when things go back to normal.”